Advent of Code 2023, Day 22

❄️ Back to Advent of Code 2023 solutions homepage ❄️

# Imports

from aoc23.utils import read_input

from copy import deepcopy

from heapq import heapify, heappop, heappush

from collections import deque, defaultdict

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

import matplotlib.colors as mcolors

import networkx as nx

input_22 = read_input(22)

Dropping the blocks

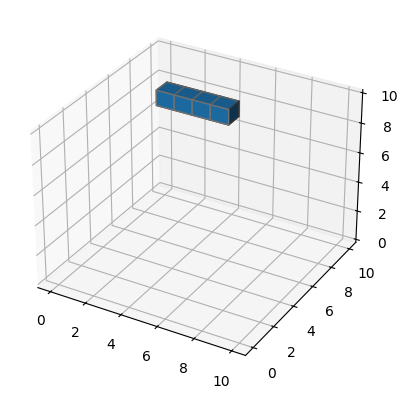

In part 1 of the day 22 puzzle, we are provided with a collection of blocks which are falling from the sky. Each block is cuboidal in shape, consisting of a line of individual cubic segments, constrained to lie on integer lattice points. The blocks are determined by the integer $(x, y, z)$ coordinates of the start and end blocks. For example, take the block defined by the first line of the input file:

input_22[0]

'2,6,9~5,6,9'

This describes a block which is $4$ units long, starting at the point $(2, 6, 9)$ and finishing at the point $(5, 6, 9)$:

# Create axis

axes = [10, 10, 10]

# Create blocks

data = np.zeros(axes)

data[2, 6, 9] = 1

data[3, 6, 9] = 1

data[4, 6, 9] = 1

data[5, 6, 9] = 1

# Plot figure

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

# Plot voxels

ax.voxels(data, edgecolors='grey')

plt.show()

|

|---|

A single block defined by 2,6,9~5,6,9, visualized as a row of cubes in 3D space. |

Let’s define a class Block to represent each block. Each block will track its component cubes, as well as the position in space where the block is located:

class Block:

def __init__(self, ends):

self.cubes = self._compute_cubes(ends)

self.length = len(self.cubes)

self.minx = min(self.cubes[0][0], self.cubes[-1][0])

self.maxx = max(self.cubes[0][0], self.cubes[-1][0])

self.miny = min(self.cubes[0][1], self.cubes[-1][1])

self.maxy = max(self.cubes[0][1], self.cubes[-1][1])

self.minz = min(self.cubes[0][2], self.cubes[-1][2])

self.maxz = max(self.cubes[0][2], self.cubes[-1][2])

self.set_id()

def __repr__(self):

return self.id

def set_id(self):

self.id = f'({self.minx}, {self.miny}, {self.minz}) -> ({self.maxx}, {self.maxy}, {self.maxz})'

@staticmethod

def _compute_cubes(ends):

# Process the input string into a list of cubes

end1, end2 = ends.split('~')

end1 = np.array([int(x) for x in end1.split(',')])

end2 = np.array([int(x) for x in end2.split(',')])

v = end2 - end1

length = max(v)

# Construct list of arrays representing cubes

blocks = [end1 + i*v/max(length, 1) for i in range(length+1)]

return sorted(blocks, key=lambda x: (x[2], x[1], x[0]))

def __lt__(self, other):

# Use z-coordinate to provide a partial ordering on the blocks

return min(self.cubes[0][2], self.cubes[-1][2]) < min(other.cubes[0][2], other.cubes[-1][2])

Demonstrating using the example from earlier:

block = Block('2,6,9~5,6,9')

block.cubes

[array([2., 6., 9.]),

array([3., 6., 9.]),

array([4., 6., 9.]),

array([5., 6., 9.])]

The blocks defined by the input file are initially floating in the air, above the ground; the first task is to ‘drop’ the blocks, so that they fall on top of each other, forming a pile which is resting on the ground (at $z=0$). We can define another class called BlockDropper, which will handle the action of dropping the blocks, and in the process creating a record of the final positions of the dropped blocks.

The strategy for dropping the blocks is to consider each block one at a time, ordered by their initial $z$-coordinate. For cuboidal blocks, this ordering will mean that no block needs to be dropped more than once. The __lt__ method of the Block class, along with a heap data structure, allows the blocks to be retrieved in this convenient order. Also, the class has a visualization function, to plot the blocks in their current states.

class BlockDropper:

def __init__(self, blocks):

self.blocks = blocks

# Allows block to be retrieved

# by increasing z-coordinate

heapify(self.blocks)

# Useful variables, to track the resting places of the drops

self.lowest_free_space = defaultdict(lambda: 1)

self.xy_entries = defaultdict(lambda: {})

self.nonzero_drops = 0

self.is_dropped = False

# Colours for visualization

self.colors = list(mcolors.TABLEAU_COLORS.keys())

def drop_blocks(self):

assert not self.is_dropped

dropped_blocks = []

self.dropped = {b.id: False for b in self.blocks}

while not all(self.dropped.values()):

# Retrieve next block

b = heappop(self.blocks)

self.dropped[b.id] = True

# Find distance to lowest unoccupied space in z-direction

drop_distance = min([cube[2] - self.lowest_free_space[(cube[0], cube[1])]

for cube in b.cubes])

# Keep track of number of blocks dropped

if drop_distance > 0:

self.nonzero_drops = self.nonzero_drops + 1

# Update the cube coordinates after drop

b.cubes = [np.array([cube[0], cube[1], cube[2] - drop_distance])

for cube in b.cubes]

# Keep track of which blocks occupy spaces in each x-y column

for cube in b.cubes:

self.xy_entries[(cube[0], cube[1])][cube[2]] = b

# Update block z information

b.minz = b.minz - drop_distance

b.maxz = b.maxz - drop_distance

b.set_id()

# Update lowest_free_space, as block now occupies current one

for cube in b.cubes:

self.lowest_free_space[(cube[0], cube[1])] = \

max(self.lowest_free_space[(cube[0], cube[1])], cube[2]) + 1

dropped_blocks.append(b)

self.is_dropped = True

self.blocks = dropped_blocks

def visualize_blocks(self, **fig_args):

# Create axes

minx = np.min([b.minx for b in self.blocks])

maxx = np.max([b.maxx for b in self.blocks])

miny = np.min([b.miny for b in self.blocks])

maxy = np.max([b.maxy for b in self.blocks])

minz = np.min([b.minz for b in self.blocks])

maxz = np.max([b.maxz for b in self.blocks])

axes = [int(maxx)+1, int(maxy)+1, int(maxz)+1]

# Create data

data = np.zeros(axes)

colors = np.empty(data.shape, dtype=object)

for i, block in enumerate(self.blocks):

for cube in block.cubes:

coords = [int(cube[0]), int(cube[1]), int(cube[2])-1]

data[*coords] = 1

colors[*coords] = self.colors[i % len(self.colors)]

# Plot figure

fig = plt.figure(**fig_args)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

ax.voxels(data, facecolors=colors, alpha=0.8)

ax.set_box_aspect((maxx-minx, maxy-miny, maxz-1))

ax.set_yticklabels([])

ax.set_xticklabels([])

ax.set_zticklabels([])

return fig, ax

The puzzle has provided us a example set of blocks, to test the drop_blocks function:

test_input = [

'1,0,1~1,2,1',

'0,0,2~2,0,2',

'0,2,3~2,2,3',

'0,0,4~0,2,4',

'2,0,5~2,2,5',

'0,1,6~2,1,6',

'1,1,8~1,1,9'

]

test_dropper = BlockDropper([Block(b) for b in test_input])

test_dropper.blocks

[(1.0, 0.0, 1.0) -> (1.0, 2.0, 1.0),

(0.0, 0.0, 2.0) -> (2.0, 0.0, 2.0),

(0.0, 2.0, 3.0) -> (2.0, 2.0, 3.0),

(0.0, 0.0, 4.0) -> (0.0, 2.0, 4.0),

(2.0, 0.0, 5.0) -> (2.0, 2.0, 5.0),

(0.0, 1.0, 6.0) -> (2.0, 1.0, 6.0),

(1.0, 1.0, 8.0) -> (1.0, 1.0, 9.0)]

test_dropper.blocks[0].cubes

[array([1., 0., 1.]), array([1., 1., 1.]), array([1., 2., 1.])]

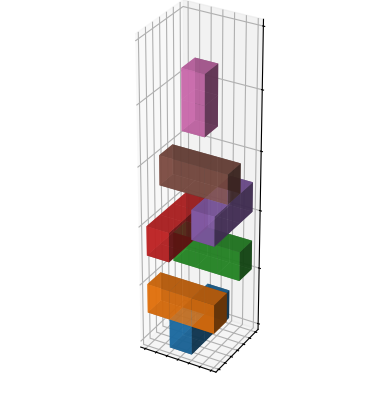

As seen here, each block consists of a list of arrays, representing the centres of each component cube. We can visualize the starting positions of all of the blocks:

fig, ax = test_dropper.visualize_blocks()

|

|---|

| Visualization of the test set of blocks, before being dropped. |

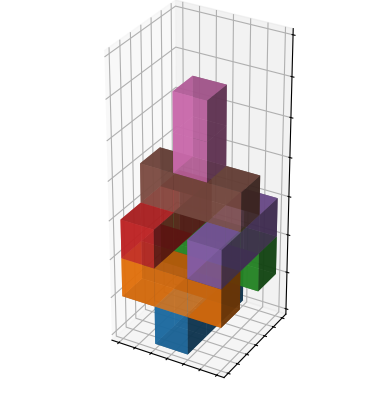

After dropping the blocks, they will rest atop each other in a stack, which itself rest on the ground (the $z=0$ plane):

test_dropper.drop_blocks()

test_dropper.blocks

[(1.0, 0.0, 1.0) -> (1.0, 2.0, 1.0),

(0.0, 0.0, 2.0) -> (2.0, 0.0, 2.0),

(0.0, 2.0, 2.0) -> (2.0, 2.0, 2.0),

(0.0, 0.0, 3.0) -> (0.0, 2.0, 3.0),

(2.0, 0.0, 3.0) -> (2.0, 2.0, 3.0),

(0.0, 1.0, 4.0) -> (2.0, 1.0, 4.0),

(1.0, 1.0, 5.0) -> (1.0, 1.0, 6.0)]

fig, ax = test_dropper.visualize_blocks()

|

|---|

| Visualization of the test set of blocks, after being dropped. |

As expected, this matches the description given in the puzzle. Let’s try this now for the full set of blocks:

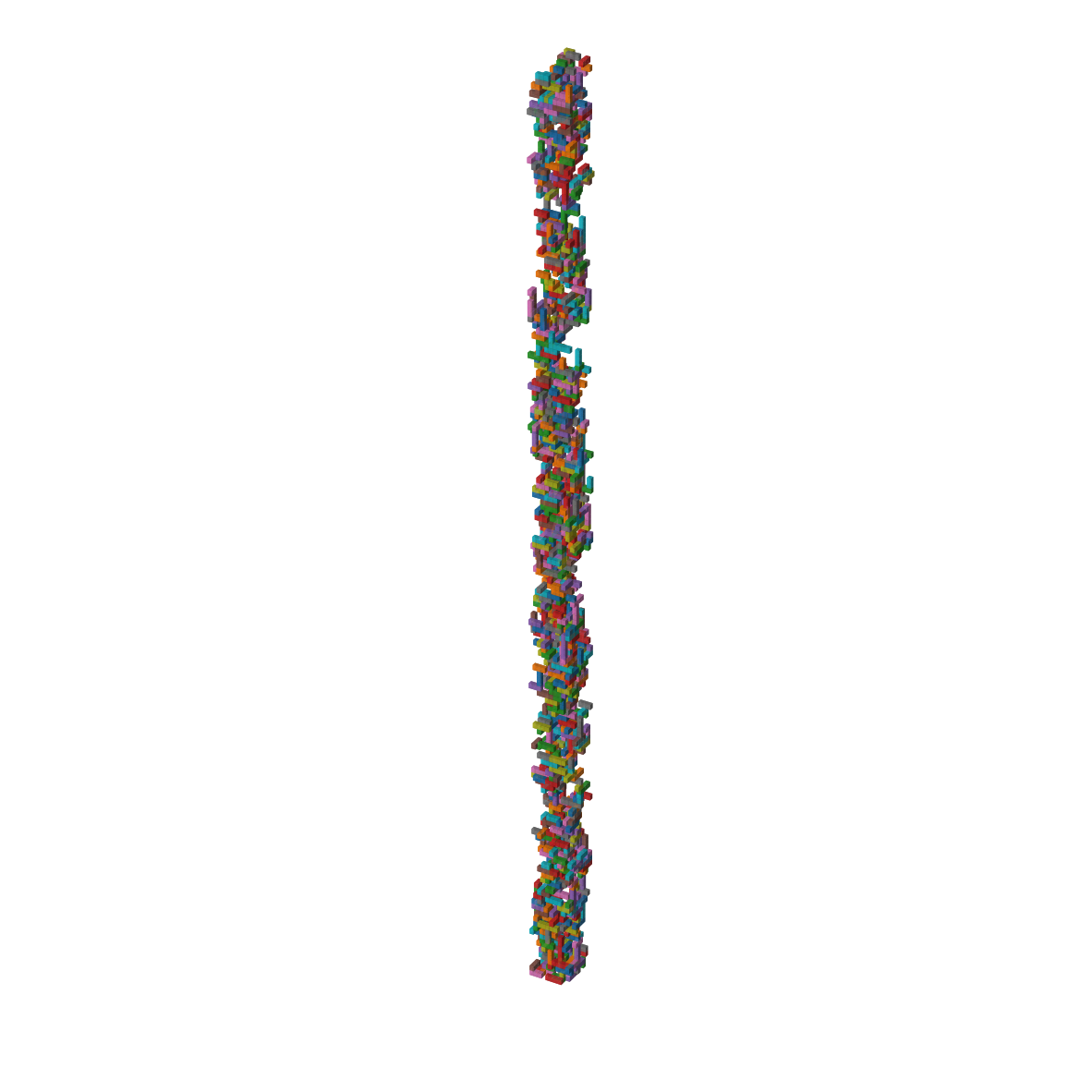

dropper = BlockDropper([Block(b) for b in input_22])

fig, ax = dropper.visualize_blocks(figsize=(15, 20))

ax.set_axis_off()

|

|---|

| Visualization of the full set of blocks, before being dropped. |

dropper.drop_blocks()

fig, ax = dropper.visualize_blocks(figsize=(15, 20))

ax.set_axis_off()

|

|---|

| Visualization of the full set of blocks, after being dropped. |

Counting the number of falling blocks

The two parts of this puzzle ask for the following:

- The number of blocks which, when disintegrated, do not result in any other blocks falling.

- For each block, the number of other blocks which fall when the block is disintegrated.

My initial thoughts for the way to compute this were to do something like the following:

disintegrate_dict = {}

# Choose a block to disintegrate

for block in dropper.blocks:

# Create a new dropper with this block removed

dropper_copy = BlockDropper([deepcopy(b) for b in dropper.blocks if b != block])

# Drop blocks and count number of blocks dropped

dropper_copy.drop_blocks()

disintegrate_dict[block.id] = dropper_copy.nonzero_drops

However, this requires creating a separate DropBlocks instance for every block in the stack, and runnning the drop_blocks methods for each of them (which itself loops over all blocks), so I quickly moved onto an alternative method.

A key insight is that the exact shapes and positions of the blocks does not really matter - what is important is the way in which the blocks lie relative to each other. In particular, all the necessary detail required is contained in a dict which maps each block to the other blocks which lie immediately on top of it (i.e. are ‘supported’ by it). Equivalently, we could construct a dict which maps each block to the other blocks which it lies on top of. The following function computes both of these objects, given a BlockDropper:

def compute_support(dropper):

# The two dicts to construct

support = {block: set() for block in dropper.blocks}

atop = {block: set() for block in dropper.blocks}

xy = dropper.xy_entries

# For each (x,y) position, find blocks which

# lie in neighbouring z slots

for x, y in xy.keys():

for z, block in xy[(x, y)].items():

if z+1 in xy[(x, y)]:

support[block].add(xy[(x, y)][z+1])

atop[xy[(x, y)][z+1]].add(block)

# Remove blocks which are in their own support/atop entry

# (happens when block is oriented vertically)

for k in support:

while k in support[k]:

support[k].remove(k)

for k in atop:

while k in atop[k]:

atop[k].remove(k)

return support, atop

test_support, test_atop = compute_support(test_dropper)

support, atop = compute_support(dropper)

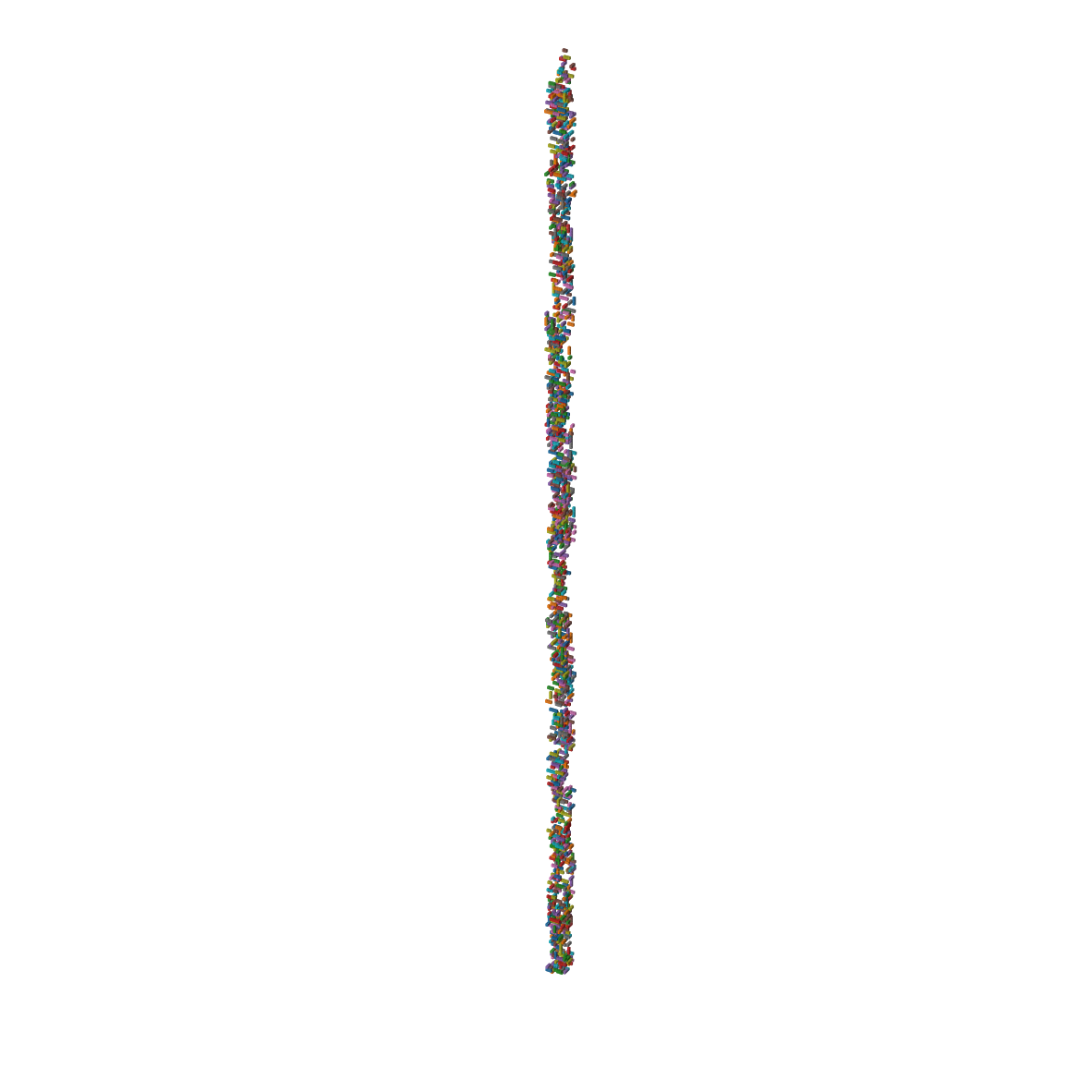

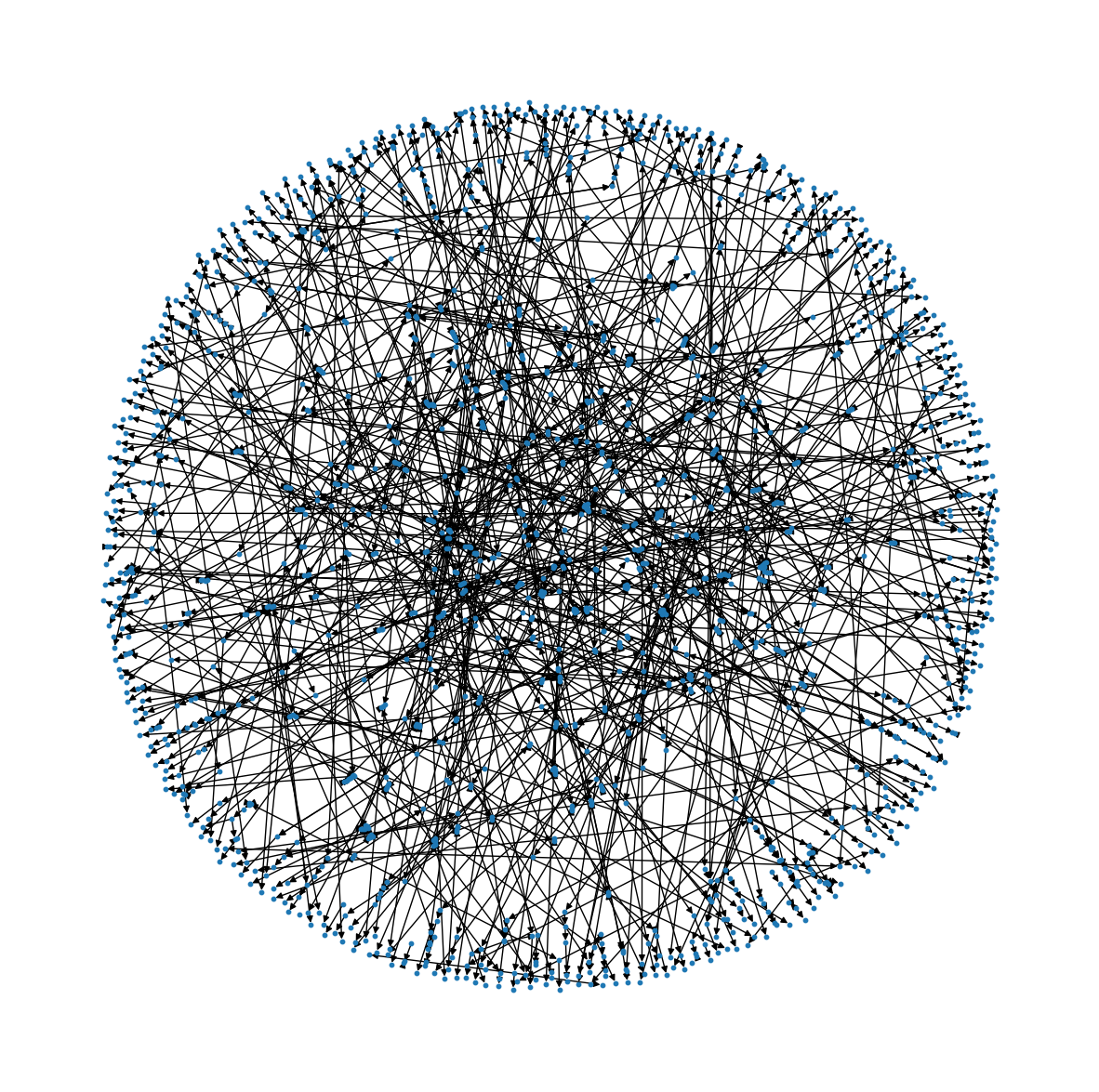

These dictionaries define directed graphs, where each node is a block and each directed edge $a\rightarrow b$ from represents a block $b$ which supports/is supported by block $a$. In fact, the directed graph defined by the support dictionary is the transpose of the directed graph defined by the atop dictionary (obtained by reversing the direction of all the directed edges). The essential structure of the blocks after they have been dropped looks like this, when visualised as as a directed graph:

graph = nx.DiGraph(support)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(15, 15))

nx.draw(graph, pos=nx.spring_layout(graph, iterations=150), node_size=10, ax=ax)

|

|---|

| The directed graph of supporting blocks. Each edge represents a block which is touching another blcok from below (in the $z$ direction). |

Given this graph representation of the blocks, how can we compute the number of blocks dependent on a specific block? It is not as simple as counting the number of nodes reachable from the block node via directed edges, as one of these nodes may also be supported by a blocks that is not dependent on the original block. The visualization of the small example set of blocks earlier illustrates this - the brown block is supported by the red block, but will not fall if the red block is disintegrated as it is also supported by the purple block.

The strategy for computing this number, given a specific block, is to use a deque to track potential blocks. The blocks also have a flag, indicating whether they are currently falling. Each time a block is retrieved from the front of the queue, it is only considered if all of the blocks that support it are also currently falling. If so, the blocks that are atop it are added to the queue and the falling flag for the block is set to True; otherwise, it is being supported by another block, so no action is taken.

def compute_n_falling(block, support, atop):

# Falling flags for all blocks

is_falling = {b: False for b in support}

# Block under consideration is

# considered to be falling

is_falling[block] = True

# Add block to queue

queue = deque(support[block])

while queue:

# Consider next block n queue

b = queue.popleft()

if all([is_falling[a] for a in atop[b]]):

# Update flag

is_falling[b] = True

# Add all dependents to queue

for c in support[b]:

queue.append(c)

# Return number of falling blocks

# (minus first block)

return sum(is_falling.values()) - 1

Let’s demonstrate this approach on the small set of example blocks we visualized earlier:

for b in test_support:

print(f'Disintegrate block {b}, causing {compute_n_falling(b, test_support, test_atop)} other blocks to fall')

Disintegrate block (1.0, 0.0, 1.0) -> (1.0, 2.0, 1.0), causing 6 other blocks to fall

Disintegrate block (0.0, 0.0, 2.0) -> (2.0, 0.0, 2.0), causing 0 other blocks to fall

Disintegrate block (0.0, 2.0, 2.0) -> (2.0, 2.0, 2.0), causing 0 other blocks to fall

Disintegrate block (0.0, 0.0, 3.0) -> (0.0, 2.0, 3.0), causing 0 other blocks to fall

Disintegrate block (2.0, 0.0, 3.0) -> (2.0, 2.0, 3.0), causing 0 other blocks to fall

Disintegrate block (0.0, 1.0, 4.0) -> (2.0, 1.0, 4.0), causing 1 other blocks to fall

Disintegrate block (1.0, 1.0, 5.0) -> (1.0, 1.0, 6.0), causing 0 other blocks to fall

As expected, the only times that blocks fall are:

- When the brown block is removed (so only the pink block falls),

- When the blue block is removed (so the 6 remaining blocks all fall).

With this function, we can count the blocks that will cause other blocks to fall when disintegrated, as well as the number of blocks that will fall:

test_falling_blocks = [compute_n_falling(b, test_support, test_atop) for b in test_dropper.blocks]

assert sum([n == 0 for n in test_falling_blocks]) == 5

assert sum(test_falling_blocks) == 7

print('Success!')

Success!

Finally, let’s repeat this for the full set of blocks:

falling_blocks = [compute_n_falling(b, support, atop) for b in dropper.blocks]

print(sum([n == 0 for n in falling_blocks]))

print(sum(falling_blocks))

512

98167

So the answer to part 1 is 512, and the answer to part 2 is 98167.

Comments